PALEOLITIC - OLD STONE AGE EGYPT

Lower Paleolithic cultures predominantly used large pear shaped or oval stone tools, often referred to as Acheulean hand axes. Unmodified flakes which were chipped from the stone core were also used for cutting. One of the oldest examples was discovered in sediment laid down by the Nile close to Abu Simbel at around 700,000 years ago. This date may not be certain, but there is firm evidence of Acheulean technology in the Western Desert at 300,000 BC.

One of the most interesting settlements from the period, Arkin 8, was discovered close to Wadi Halfa near the modern border with Sudan. It seems to have been a temporary camp, possibly used seasonally. It was not very well preserved, but did provide an impressive number of artifacts (predominantly pebble like tools) and a structure thought to date to around 100,000BC. Composed of a series of sandstone blocks set in a semi-circle with a 180 cm by 120 cm oval foundation dug 30 cm deep, it is one of the earliest structures to be found anywhere in the world.

| These stone tools were made by hominins who lived in Egypt around half a million years ago, making them around 495,000 years older than the earliest ‘Egyptians’. It’s likely that Egypt was occupied by hominins during cooler periods when river systems and vegetation provided a suitable habitat. Lots of these handaxes were found on river terraces suggesting these waterways were an important part of life. Petrie Museum |

|

Upper Paleolithic, 35,000 before present; National Museum of Egyptian Civilization, Cairo. |

|

Upper Paleolithic, 35,000 before present; National Museum of Egyptian Civilization, Cairo. |

THE RISE OF EGYPTIAN CIVILIZATION

Paleolithic to Protodynastic

|

Stone vessels found in tombs of the Naqada Period |

The LATE PALEOLITHIC featured mobile buildings and tool-making industry. This period began around 30,000 BC. Ancient, mobile buildings, capable of being disassembled and reassembled were found along the southern border near Wadi Halfa. Aterian tool-making industry reached Egypt around 40,000 BC and Khormusan industry began between 40,000 and 30,000 BC

The MESOLITHIC saw the rise of various

cultures including Halfan, Qadan, Sebilian and Harifian. Halfan

culture arose along the Nile Valley of Egypt and in Nubia between

18,000 and 15,000 BC. They appeared to be settled people, descended

from the Khormusan people and spawned the Ibero-Marusian industry.

Material remains from these people include stone tools, flakes,

and rock paintings.

The Qadan culture practiced wild-grain harvesting along the Nile and developed sickles and grinding stones to collect and process these plants. These people were likely residents of Libya who were pushed into the Nile Valley due to desiccation in the Sahara. The Sebilian culture gathered wheat and barley.

The Harifian culture migrated out of the Fayyum and the Eastern deserts of Egypt to merge with the Pre-Pottery Neolithic B; this created the Circum-Arabian Nomadic Pastoral Complex who invented nomadic pastoralism and may have spread Proto-Semitic language throughout Mesopotamia.

The NEOLITHIC saw the rise of cultures

including Merimde, El Omari, Maadi, Tasian and Badarian. Expansion

of the Sahara desert forced more people to settle around the

Nile in a sedentary, agriculture-based lifestyle. Around 6000

BC Neolithic settlements began to appear in great number in this

area, likely as migrants from the Fertile Crescent returned to

the area. Weaving occurred for the first time in this period

and people buried their dead close to or within their settlements.

The Merimde culture (5000-4200 BC) was located in Lower Egypt. People lived in small huts, created simple pottery and had stone tools. They had cattle, sheep, goats and pigs and planted wheat, sorghum and barley. The first Egyptian life-size clay head comes from this culture.

The El Omari culture (4000-3100 BC) lived near modern-day Cairo. People lived in huts, and had undecorated pottery and stone tools. Metal was unknown.

The Maadi culture is the most important Lower Egyptian prehistoric culture. Copper was used, pottery was simple and undecorated and people lived in huts. The dead were buried in cemeteries.

The Tasian culture (4500-3100 BC) produced a kind of red, brown and black pottery called blacktop-ware. From this period on Upper Egypt was strongly influenced by the culture of Lower Egypt.

The Badarian culture (4400-4000 BC) was similar to the Tasian except they improved blacktop-ware and used copper in addition to stone.

The Amratian culture (Naqada I) (4000-3500 BC) continued making blacktop-ware and added white cross-line-ware which featured pottery with close, parallel, white, crossed lines. Mud-brick buildings were first seen in this period in small numbers.

| Amratian (Naqada I) Terracotta Figure. This terracotta female figure, c. 3500-3400 BCE, is housed at the Brooklyn Museum. |

The Gerzean culture (Naqada II, 3500-3200 BC) saw the laying of the foundation for Dynastic Egypt. It developed out of Amratian culture, moving south through Upper Egypt. Its pottery was painted dark red with pictures of animals, people and ships. Life was increasingly sedentary and focused on agriculture as cities began to grow. Mud bricks were mass-produced, copper was used for tools and weapons and silver, gold, lapis and faience were used as decorations. The first Egyptian-style tombs were built.

Protodynastic Period (Naqada III) (3200 – 3000 BC)

During this period the process of state formation, begun in Naqada II, became clearer. Kings headed up powerful polities but they were unrelated. Political unification was underway which culminated in the formation of a single state in the Early Dynastic Period. Hieroglyphs may have first been used in this period along with irrigation. Additionally royal cemeteries and serekhs (royal crests) came into use.

Three phases of Naqada culture included: the rise of new types of pottery (including blacktop-ware and white cross-line-ware), the use of mud-bricks and increasingly sedentary lifestyles.

During the Protodynastic period (3200-3000 BC) powerful kings

were in place, and unification of the state occurred, which led

to the Early Dynastic Period.

The powerful civilization of ancient Egypt took just a few centuries to build, according to a radiocarbon dating study that sets the first solid chronology for the period. Five thousand years ago, Egypt became the world’s first territorial state with strict borders, organised religion, centralized administration and intensive agriculture. It lasted for millennia and set a template that countries still follow today. Archaeologists have assumed it developed gradually from the pastoral communities that preceded it but physicist Mike Dee from the University of Oxford and his colleagues now suggest that the transition could have taken as little as 600 years. The early history of ancient Egypt is murky because although there are plenty of archaeological finds including royal tombs there is no reliable way to attribute firm dates to the various reigns and periods. Radiocarbon dating has previously been of limited use because dating individual objects gives ranges of up to 300 years ---- The researchers used carbon dating to estimate with 68 per cent probability that the first ruler, King Aha, took to the throne between 3111 and 3045 BC, and died between 3073 and 3036 BC. They concluded that the Predynastic period began in 3800-3700 BC so it lasted just 600-700 years, several centuries less than previously thought. This is a period during which Egypt goes through a major transition. It started with small, cattle-owning communities who migrated with the seasons. At the end you’ve got a state. “All the important things that our societies do were invented then”

Radiocarbon dating verifies ancient Egypt's history

2010

The world’s oldest woven garment, called the Tarkhan Dress (3482-3102 BC), probably fell past the knees originally. At 5100 to 5500 years old, it dates to the dawn of the kingdom of Egypt.

Necropolis Umm el-Qaab at Abydos

FIRST AND SECOND DYNASTIES

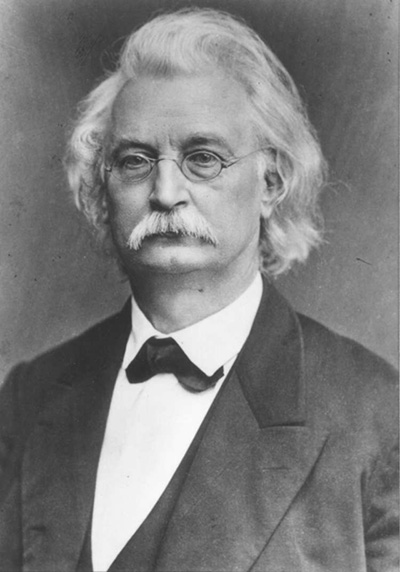

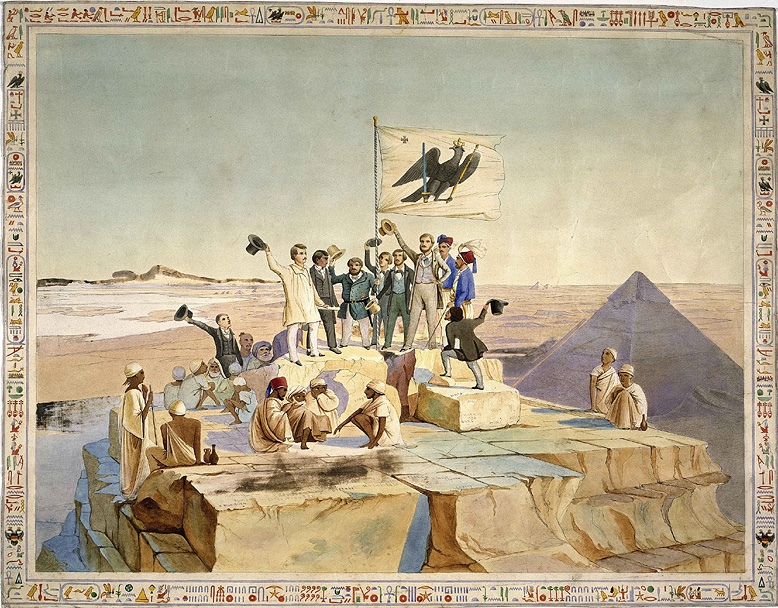

| Denkmäler aus Ägypten und Äthiopien (literally "Monuments from Egypt and Ethiopia", where "Ethiopia" was then a synonym for Nubia) is a monumental work by Karl Richard Lepsius published in Prussia in 1849–1859. Like the French Description de l'Égypte, published forty years previously, the work is still regularly consulted by Egyptologists today. |

|

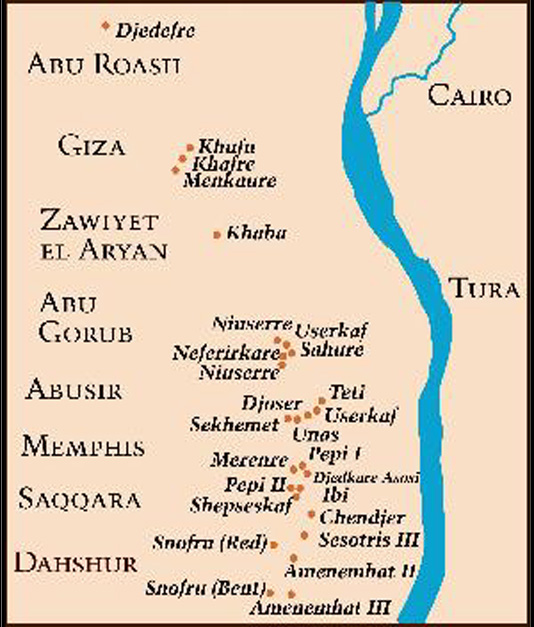

It records the scientific documentation obtained by Lepsius's Prussian expedition to Egypt and Nubia from 1842–1845 in order to gather knowledge about the local monuments of ancient Egyptian civilization. This expedition was modelled after the earlier Napoléonic mission and consisted of surveyors, draftsmen and other specialists. The mission reached Giza in November 1842 and spent six months making some of the first scientific studies of the pyramids of Giza, Abusir, Saqqara and Dahshur. They discovered 67 pyramids, recorded in the pioneering Lepsius list of pyramids, and more than 130 tombs. During the mission, the Prussian team collected around 15,000 objects and plaster casts which today form the core of the collection of the Egyptian Museum of Berlin. The work was published in twelve large-format volumes, later supplemented by five volumes of notes. It contains highly accurate maps for its time, as well as nearly 900 plates of monuments and copies of inscriptions. |

| The Prussian expedition assembled in Alexandria in 1842 and quickly departed for Giza, which was reached in November that same year. Proceeding north to south, Lepsius's men then explored the pyramids field of Abusir, Saqqara, Dahshur and, in 1843, Hawara. Lepsius and team stayed for 6 months in total at these locations, as the Prussian expedition was the first to study and record Old Kingdom material in depth. |

|

The Prussian expedition assembled in Alexandria in 1842 and quickly departed for Giza which was reached in November that same year. Proceeding north to south, Lepsius's men then explored the pyramids field of Abusir, Saqqara, Dahshur and in 1843, Hawara. Lepsius and team stayed for 6 months in total at these locations, as the Prussian expedition was the first to study and record Old Kingdom material in depth. In total Lepsius and his men uncovered a total of 67 pyramids and 130 tombs. The pyramids, dating from the Third Dynasty c. 2686–2613 BC until the Thirteenth Dynasty c. 1800–1650 BC were given Roman numerals from north to south starting from Abu Rawash in the north. Although a few of the structures reported by Lepsius are now known to have been mastabas and other monumental structures the Lepsius list of pyramids is still considered a pioneering achievement of modern Egyptology. Lepsius' numerals have remained the standard designation for some of the pyramids. |

Madain Project

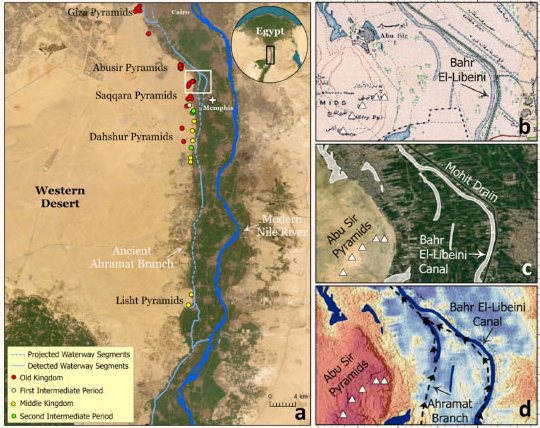

Majority of Egyptian Pyramids Was Built along Long-Lost Branch of Nile, Archaeologists Say

May 21, 2024

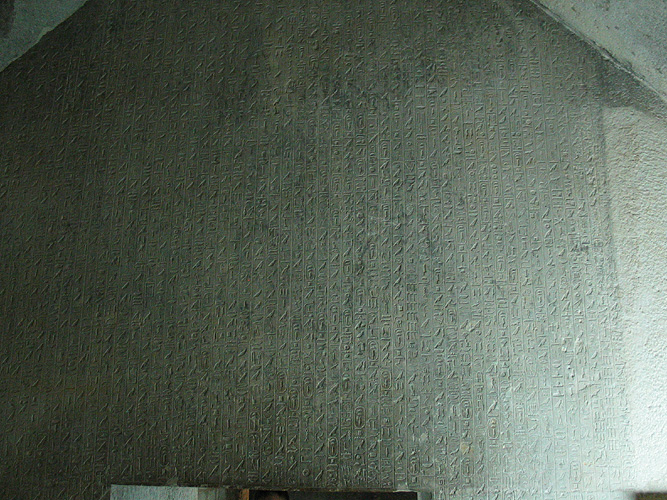

DISCOVERY OF THE PYRAMID TEXTS

DISCOVERY OF THE PYRAMID TEXTS

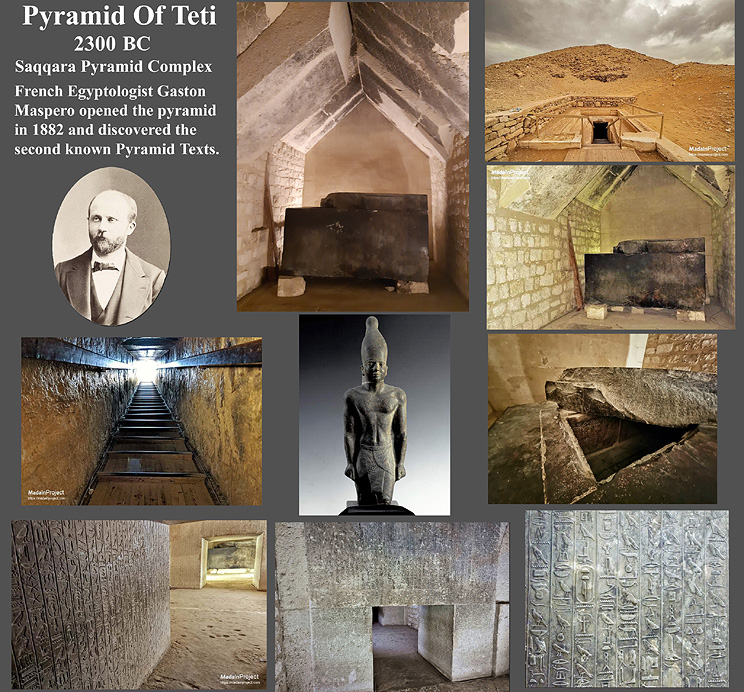

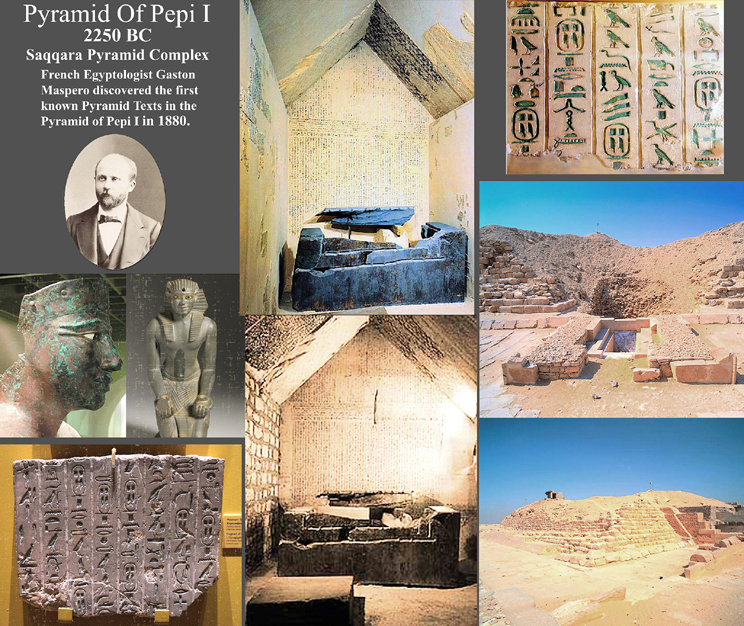

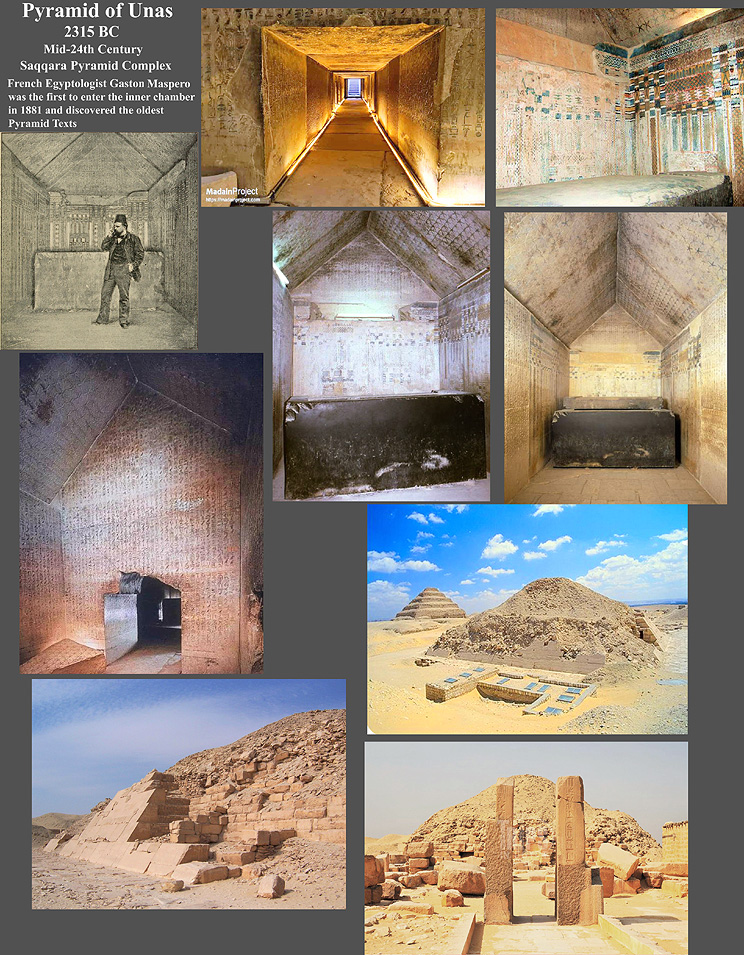

Maspero continued his excavations at a second structure, around one kilometer/0.62 mile south-west of the first in search of more evidence. This second structure was determined to be the pyramid of Merenre I, Pepi I's successor. In it, Maspero discovered the same hieroglyphic text on the walls he had found in Pepi I's pyramid and the mummy of a man in the sarcophagus of the burial chamber. This time he visited Mariette personally who again rejected the findings, saying on his deathbed that "in thirty years of Egyptian excavations I have never seen a pyramid whose underground rooms had hieroglyphs written on their walls." Throughout 1881 Maspero continued to direct investigations of other sites in Saqqara and more texts were found in each of the pyramids of Unas, Teti and Pepi II. Maspero began publishing his findings in the Recueil des Travaux from 1882 and continued to be involved until 1886 in the excavations of the pyramid in which the texts had been found.

Maspero also found texts in the pyramids of Unas, Teti, Merenre I, and Pepi II in 1880–1.[23] He published his findings in Les inscriptions des pyramides de Saqqarah in 1894

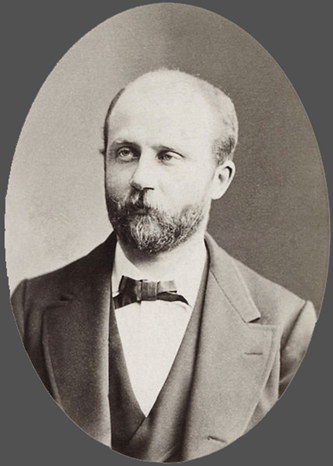

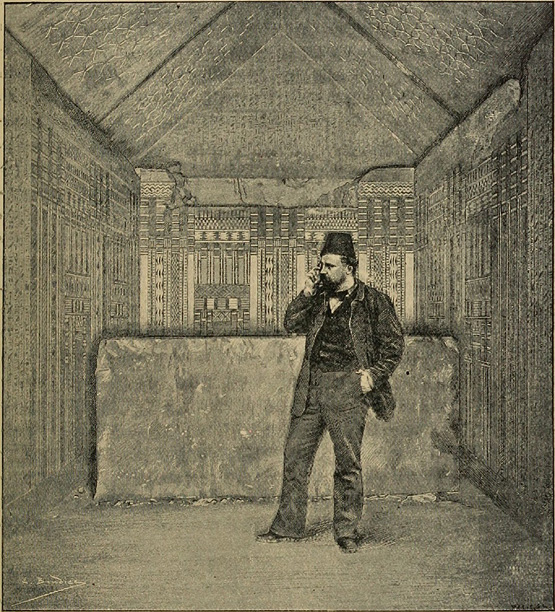

Maspero in the burial chamber of Unas' pyramid, which has lines of protective spells on the west gable, which are the only inscriptions on the walls surrounding the sarcophagus

The underground chambers remained unexplored until 1881, when Gaston Maspero, who had recently discovered inscribed texts in the pyramids of Pepi I and Merenre I, gained entry. Maspero found the same texts inscribed on the walls of Unas's pyramid, their first known appearance. The 283 spells in Unas's pyramid constitute the oldest, smallest and best preserved corpus of religious writing from the Old Kingdom.

Saqqara

Unas was the first pharaoh to have the Pyramid Texts carved and painted on the walls of the chambers of his pyramid, a major innovation that was followed by his successors until the First Intermediate Period (c.?2160 – c.?2050 BC).

The reopening of the Unas pyramid is part of a larger plan of the Egyptian Ministry of Antiquities to open more archaeological sites to attract tourists.

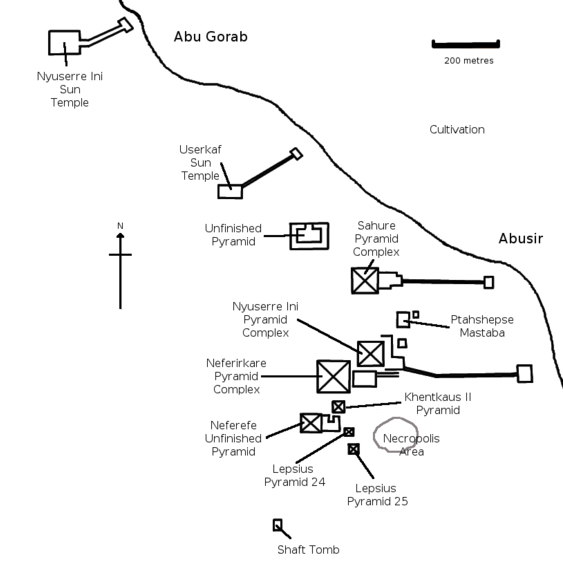

‘’We’re planning to make other sites at the Abusir necropolis accessible to the public, like the tomb of Vizier Ptahshepses, the pyramids of Sahura and Neferirkare,’’ said Sabry Farag, director of the Saqqara and Abusir necropolis sites.

Saqqara

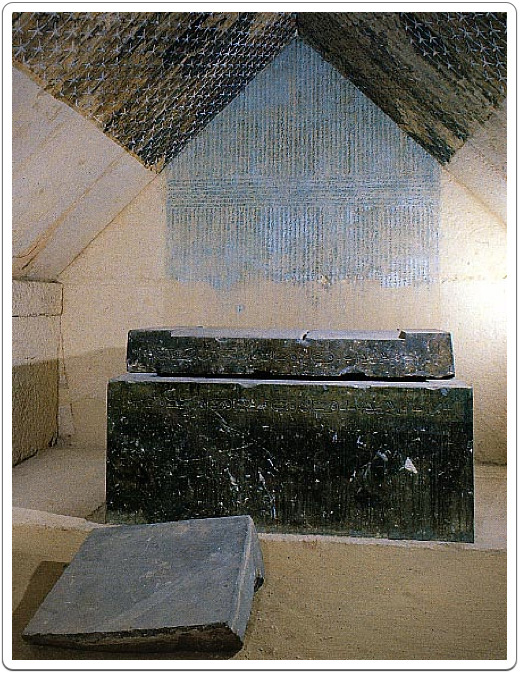

| The burial chamber contains an unfinished greywacke sarcophagus, a fragment of a lid and a canopic container that is nothing more than a simple hole in the ground. And for the first time, a royal sarcophagus contains inscriptions, here slightly etched on the hollow interior of the vessel. The burial chamber and the antechamber are covered with huge vaulted rafters. The walls of the burial chamber and the antechamber are covered with hieroglyhic inscriptions commonly called the Pyramid Texts. |

Pyramid of Teti poster full size

Saqqara

Saqqara

|

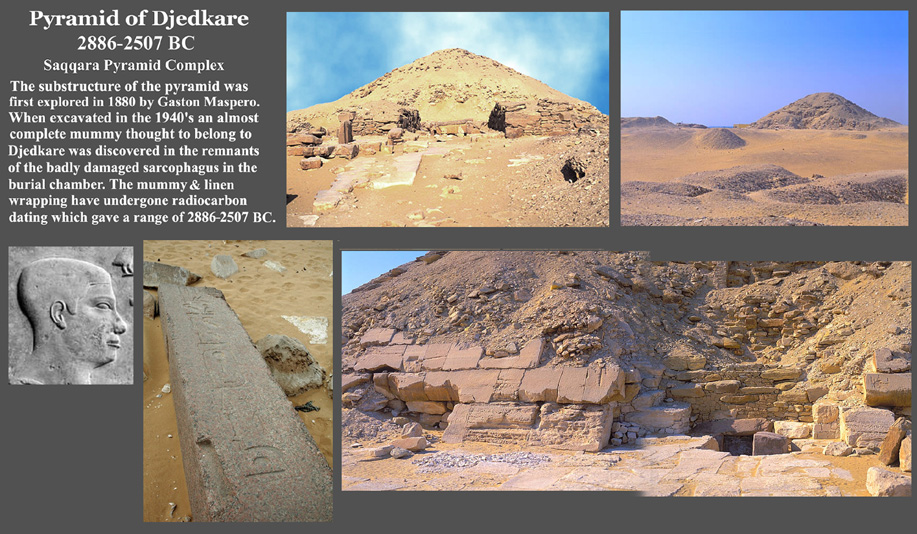

The basalt sarcophagus was badly destroyed when it was found, but enough fragments have been found to allow for its reconstruction. A niche for the canopic chest was sunk into the floor and concealed by a slab, which didn't prevent it from getting looted. None of the inner rooms of the pyramid appears to have been inscribed. In the burial chamber pieces of alabaster and a faience bead on a gold thread were discovered, as well as many fragments of what was originally a large sarcophagus of dark grey basalt. The sarcophagus was sunk into the floor of the burial chamber and there was a niche for the canopic chest of the king to its north-east. An almost complete mummy was discovered in the remnants of the sarcophagus. An examination by Ahmed Batrawi of these skeletal remains, excavated in the mid-1940s under the direction of Abdel-Salam Hussein, suggests that Djedkare died at the age of 50 to 60 years. Inside Djedkare Isesi's pyramid substructure, remains of the burial have been found alongside the mummy remains of Djedkare Isesi himself. The mummy and linen wrapping have undergone radiocarbon dating which have given a common range of 2886–2507 BC. The substructure has otherwise been badly damaged by stone thieves quarrying the Tura limestone casing. |

PYRAMID OF DJEDKARE POSTER FULL SIZE

|

Djedkare is believed to have been buried in a pyramid in Saqqara named Nefer Djedkare ("Djedkare is perfect"), which is now ruined owing to theft of stone from its outer casing during antiquity. When excavated in the 1940's the burial chamber contained mummified skeletal remains thought to belong to Djedkare. Examinations of the mummy revealed the individual died in his 50's. A clue to the identity of the remains came from skeletal and blood type comparisons with those of two females thought to be Djedkare's daughters buried in the nearby Southern Cemetery at Abusir. Radiocarbon dating carried out on the effects of the three individuals revealed a common range of 2886-2507 BC, some 160–390 years older than the accepted chronology of the 5th Dynasty. The pyramid was briefly visited by John Shae Perring and soon after that by Karl Richard Lepsius. The substructure of the pyramid was first explored in 1880 by Gaston Maspero. In the mid-1940s, Alexandre Varille and Abdel Salam Hussein attempted the first comprehensive examination of the pyramid, but their work was interrupted and their findings lost. They did discover the skeletal remains of Djedkare Isesi in the pyramid. Ahmed Fakhry's attempt at a comprehensive examination in the 1950s was equally unsuccessful. Relief fragments that Fakhry had discovered were later published by Muhammud Mursi. |

Saqqara

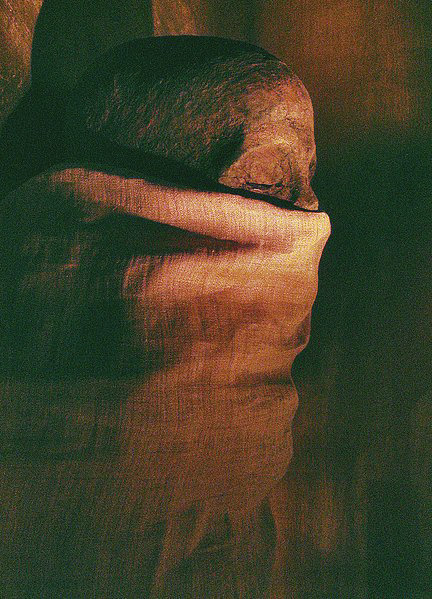

The burial chamber contained a black basalt sarcophagus, which was intact when it was discovered and even its lid, although pushed back, was mainly unbroken. The mummy that was discovered inside this sarcophagus is held by some to have been Merenre I himself, alhough it is more likely that it belonged to an 18th Dynasty intrusive burial.

Merenre was probably buried in his pyramid at South Saqqara though apparently because of his unexpected death this pyramid was not yet completed. Until fairly recently it was believed that the first ever mummy was that of Merenre I though in reality the mummy found in his pyramid may not have been that of Merenre. Nevertheless in 1997 excavations began at Hierakonopolis revealing a large predyanstic cemetery full of older mummies. However, if the mummy is indeed that of Merenre, it would remain the oldest know royal mummy.

PYRAMID OFMERENRE POSTER FULL SIZE

In 1881 the Egyptologists Émile and Heinrich Karl Brugsch managed to enter the burial chamber of Merenre's pyramid via a robber's tunnel. They found its massive ceiling beams of limestone hanging dangerously as the lower retaining walls of the chamber had been removed by stone robbers. The black basalt sarcophagus was still intact, its lid pushed back, and in it lay the mummy of a 5.4 foot tall / 1.66 meter man. The mummy was in a poor condition because ancient tomb robbers had partially torn off its wrappings. The Brugsch brothers decided to transport the mummy to Cairo in order to show it to Auguste Mariette, head of the Egyptian Department of Antiquities and by then dying. During the transport the mummy suffered further damage: problems with the railroads prevented the mummy from being taken to Cairo by train and the Brugschs took the decision to carry it on foot. After the wooden sarcophagus employed to that end had become too heavy, they took out the mummy and broke it into two pieces. Parts of the mummy including the head remained in the Boulaq Cairo neighborhood until they were moved to the nearby Egyptian Museum. Émile Brugsch donated some of the rest, a collarbone, cervical vertebrae and a rib to the Egyptian Museum of Berlin. These have not been located since World War II.

Abusir

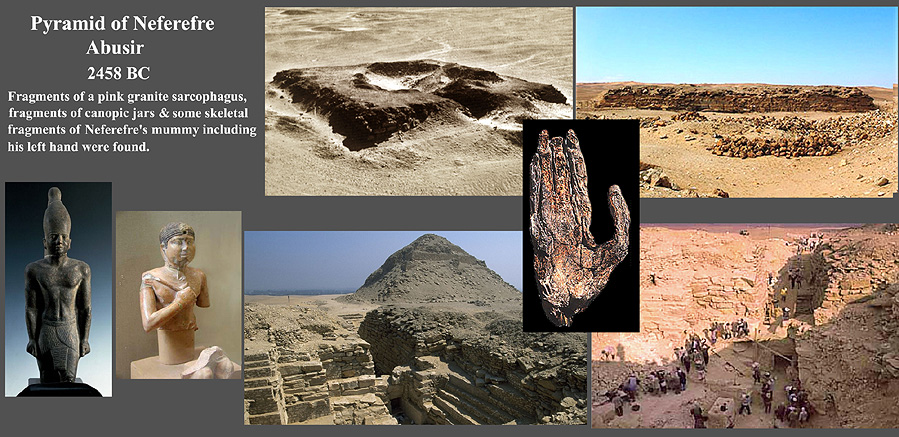

Died around 2458 BC

Abusir Pyramid of Neferefre info

Complex remains one of the best preserved of the Old Kingdom. In its substructure, excavators found fragments of a red granite sarcophagus and of Neferefre's mummy who was found to have died at around twenty to twenty-three years of age.

Archaeologists found very few contents within the tomb. The tomb was lined and sealed with pink granite. It contained parts of a pink sarcophagus, alabaster Canopic jars, alabaster offering containers and the remnants of a mummy. Upon investigation, archaeologists believe the mummy to be that of King Neferefre. He was probably between 20 to 23 years old at the time of death.

While exploring

ruins of the mortuary complex Czech archeological mission discovered

among others papyri of temple accounts, statues of the king,

decorated plates and many seal prints. In 1980 Czech archaeologists

found five small fragments of human bones in the eastern half

of the burial chamber. Survey have shown that these are the remains

of a man aged 20-23, probably pharaoh Neferefre and fragments

of a red granite sarcophagus.

The oldest would appear to be the Old Kingdom pharaoh Neferefre (5th dynasty) who is estimated to have died around 2458 BC. When found the tomb was lined and sealed with pink granite. It contained parts of a pink sarcophagus, alabaster Canopic jars, alabaster offering containers and the remnants of a mummy.

Few traces remain of the king's funerary equipment: some fragments of a red granite sarcophagus, fragments of alabaster canopic jars and some skeletal fragments of the king's mummy, including his left hand. From the few remains of his body, it has been determined that the king died at the age of about 22 or 23 years old.

Today the pyramid appears as a low mound just south of the pyramid of Neferirkare. He was the eldest son of pharaoh Neferirkare

Instead of a traditional location, Neferefre's mortuary temple stretches alongside his unfinished pyramid.

The large number of papyri, frit tables and faience ornaments found within the temple’s storage magazines more than doubled the number of documents dating to the Old Kingdom.

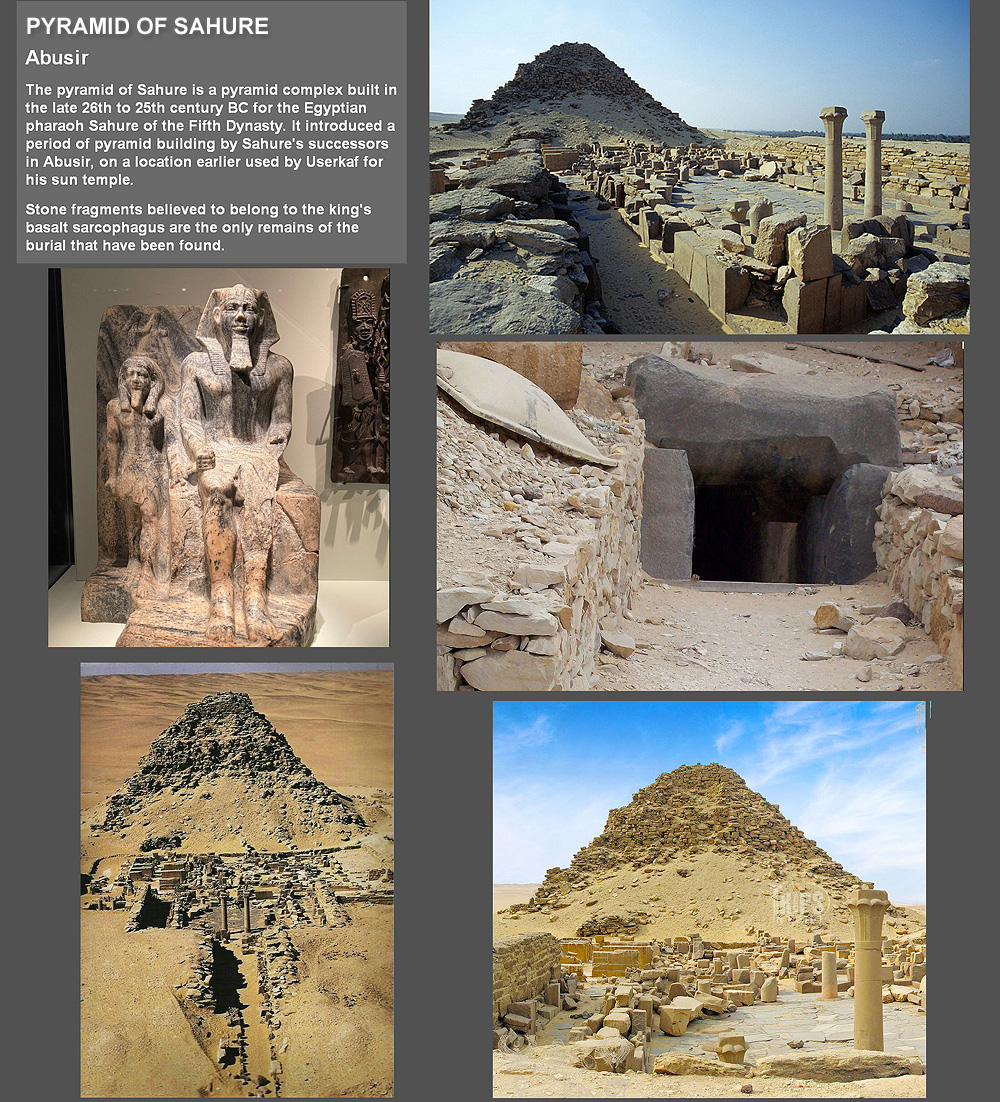

Abusir

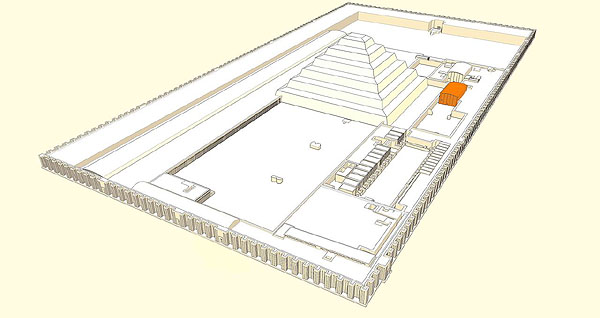

The pyramid of Sahure is a pyramid complex built in the late 26th to 25th century BC for the Egyptian pharaoh Sahure of the Fifth Dynasty. It introduced a period of pyramid building by Sahure's successors in Abusir, on a location earlier used by Userkaf for his sun temple.

Stone fragments believed to belong to the king's basalt sarcophagus are the only remains of the burial that have been found.

Inside the apartment's ruins, Perring found stone fragments - constituting the only discovered remains of the burial - which he believed belonged to the king's basalt sarcophagus.

Abusir

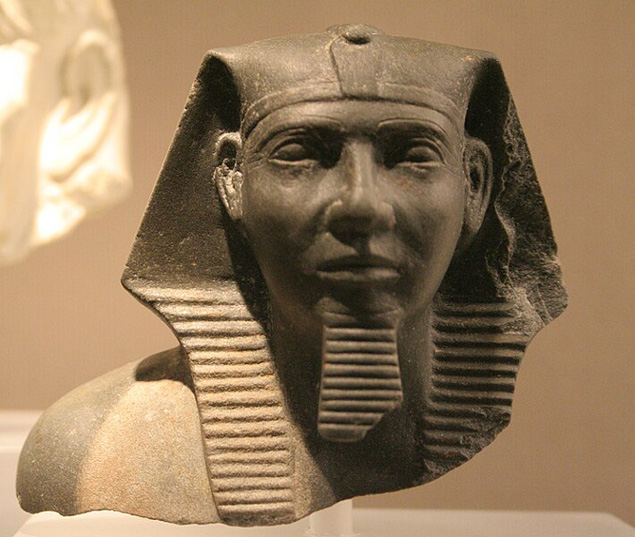

Neferirkare Kakai, Third King of the Old Kingdom 5th Dynasty

The substructure is badly damaged: the collapse of a layer of the limestone beams has covered the burial chamber. No trace of the mummy, sarcophagus or any burial equipment has been found inside. The severity of the damage to the substructure prevents further excavation.

Papyrus found in his pyramid complex were written in ink and are the earliest known documents in hieratic script, a cursive form of hieroglyphics.

| The pyramid of Neferirkare was built for the Fifth Dynasty pharaoh Neferirkare Kakai in the 25th century BC. It was the tallest structure on the highest site at the necropolis of Abusir found between Giza and Saqqara and still towers over the necropolis. The pyramid is also significant because its excavation led to the discovery of the Abusir Papyri. |

This pyramid was built by Sesostris II

The Granite Box in the Pyramid at Lahun (Part 1)

Oddities Within The Lahun Pyramid

|

The burial chamber continues along the axis of the antechamber. Clad entirely in granite and with a garbled roof, it measures 5 by 3 metres and is 3 metres high. The red granite sarcophagus was placed at the far end of the burial chamber. A small chamber opens to the south of the burial chamber. It is here that the only remains of the burial were found: a golden uraeus that once adorned the king's head and some leg bones, perhaps the king's. It is considered the first of the giant mud brick pyramids. It had a length of 106 meters, a slope of 42 35 and a height of 48.6 meters.. The structure of the pyramid is supported with a natural rocky core that was cut to accept a pyramid top, large limestone cross walls provided support for the brick sectors, which were then cased in limestone |

LAHUN

LAHUN

| The south face of the pyramid. Here you can see the mudbrick core of the pyramid, the casing stripped away in ancient times. Some of the core radiating limestone are visible. |

PYRAMID OF NIUSSERE

PYRAMID OF MENKAUHOR

"Headless Pyramid" - Saqqara

Saqqara

The identity of the pyramid owner is unclear though it is suspected to belong to either Pharaoh Menkauhor of the Fifth Dynasty or Pharaoh Merikare of the Tenth Dynasty, both of whom are known to have built a pyramid

It's substructure was thoroughly investigated between 2005 and 2008 by a team of archaeologists led by Zahi Hawass. Their findings included lowered portcullis gates indicating a burial had taken place, a sarcophagus lid built of schist and holes cut into the burial chamber floor presumed to have held canopic jars.

Inside the burial chamber, the intact lid of a sarcophagus made of grey schist was uncovered. The lid measured 8.7 feet/ 2.65 meters by 3.6 feet/1.09 m and was found covering holes cut in the floor presumed to have held canopic jars.

Menkauhor's

"Headless Pyramid"

North Saqqara

The completely destroyed pyramid in North Saqqara, which lies on the farthest edge of the desert plateau east of Teti's mortuary temple, is sometimes attributed to Menkauhor. Local people named its "Headless Pyramid". In the rubble of the pit for the burial chamber Maspero found fragments of pink granite and even a sarcophagus lid of bluish gray stone.

PYRAMID OF SEKHEMKHET

The pyramid's interior features a network of passageways, chambers, and corridors adorned with intricate hieroglyphic inscriptions and reliefs. These inscriptions provide valuable clues about ancient religious practices, burial rituals and the pharaoh's journey to the afterlife. Archaeological excavations within the pyramid have uncovered artifacts including funerary objects and human remains, shedding further light on ancient Egyptian culture and customs.

Sekhemkhet's pyramid is sometimes referred to as the "Buried Pyramid" and was first excavated in 1952 by Egyptian archaeologist Zakaria Goneim. A sealed sarcophagus was discovered beneath the pyramid, but when opened was found to be empty.

The burial chamber was left unfinished but surprisingly a nearly completely arranged burial was found. The sarcophagus in the midst of the chamber is made of polished alabaster and shows an unusual feature: its opening lies on the front side and is sealed by a sliding door which was still plastered with mortar when the sarcophagus was found. The sarcophagus was empty however and it remains unclear whether the site was ransacked after burial or whether King Sekhemkhet was buried elsewhere.

The unfinished pyramid of Zoser’s successor Sekhemkhet (2648–2640 BC) is closed to the public because of its dangerous condition. An unused travertine sarcophagus was found in the sealed burial chamber, and a quantity of gold and jewellery and a child’s body were discovered in the south tomb. Recent surveys have also revealed another mysterious large complex to the west of Sekhemkhet’s enclosure, but this remains unexcavated.

|

Mysterious sarcophagus of Sekhemkhet said to have been carved from one solid block of ‘Egyptian alabaster’ with sliding door. Dated from 2649 – 2643 BC "In the middle of a rough-cut chamber lay a magnificent sarcophagus of pale golden, translucent alabaster" under the Sekhemkhet Pyramid at Saqqara.” The only opening was sliding panel at one end, slid into position from the top. When found in 1954 the box was completely sealed--and no body was found inside. The pyramid was so named because they found the title "Sekhemkhet" on the lids of jars found at the same location. |

Hawara

|

The sandstone sarcophagus was set into the floor against the west wall. When Petrie examined the sarcophagus in Amenemhet's burial chamber, he discovered the remains of a burned inner coffin. It is believed that the coffin was damaged by ancient grave-robbers. |

Saqqara

Djoser Funerary Complex

The painted limestone statue of Djoser, now in the Egyptian Museum in Cairo, is the oldest known life-sized Egyptian statue. Today, at the site in Saqqara where it was found, a plaster copy of it stands in place of the original. The statue was discovered during the Antiquities Service Excavations of 1924–1925.

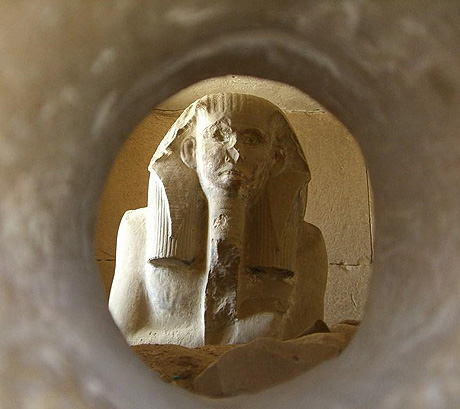

The pharaoh Djoser's Ka statue peers out through the hole in his serdab, ready to receive the soul of the deceased and any offerings presented to it.

| Detail of a relief showing Sneferu wearing the white robe of the Sed-festival, from his funerary temple of Dahshur and now on display at the Egyptian Museum |

| The only completely preserved portrait of the king is a three-inch-high ivory figurine found in a temple ruin of a later period at Abydos in 1903. All other reliefs and statues were found in fragments, and many buildings of Khufu are lost. Everything known about Khufu comes from inscriptions in his necropolis at Giza and later documents. For example, Khufu is the main character noted in the Westcar Papyrus from the 13th dynasty. |

Revealing a Hidden Tomb: A Look at Excavations inside the Tomb of Senwosret III

South Abydos

This is the tomb of pharaoh Senwosret III who reigned ca. 1878–1841 BC, 5th king of the powerful 12th Dynasty. Measured by length it is Egypt’s largest tomb, stretching 800 feet from its entrance to its inner chamber. The tomb has no aboveground superstructure: it is entirely a subterranean monument cut into the bedrock and lined with finely cut masonry. It is also a monument that still presents many questions to be answered and mysteries to be solved.

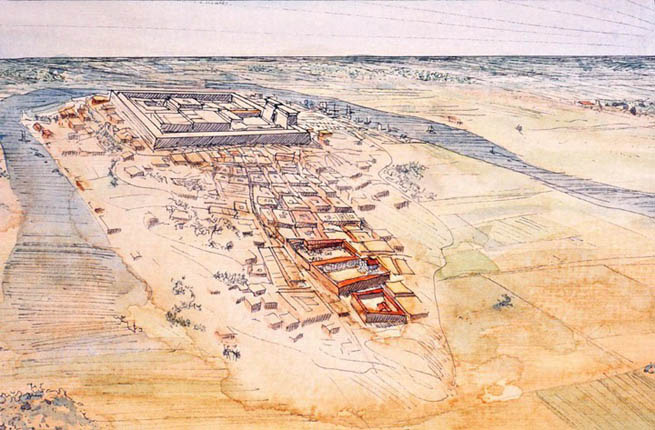

Mortuary Complex of Pharaoh Senwosret III at South Abydos

Since 2008 a key priority of the archaeological program has been the excavation and documentation of the 180-meter long subterranean tomb of Senwosret III. This structure – the first known example of a hidden royal tomb in Egyptian history – is a masterpiece of pharaonic architecture and engineering.

Royal necropolis that developed during the late Middle Kingdom around the tomb enclosure of Senwoset III. Named the “Mountain of Anubis” in ancient times based on a prominent peak in the high desert cliffs, the tomb enclosure of Senwosret III developed into the nucleus for a royal necropolis that includes tombs of eleven kings of the 13th Dynasty and Second Intermediate Period.

Naophorous Block Statue of a Governor of Sais, Psamtikseneb

Period: Late Period, Saite

Dynasty: Dynasty 26

Date: 664–610 B.C.

Geography: Possibly from Italy, Southern Europe, Tivoli, Hadrian's Villa

Dec. 12, 2019

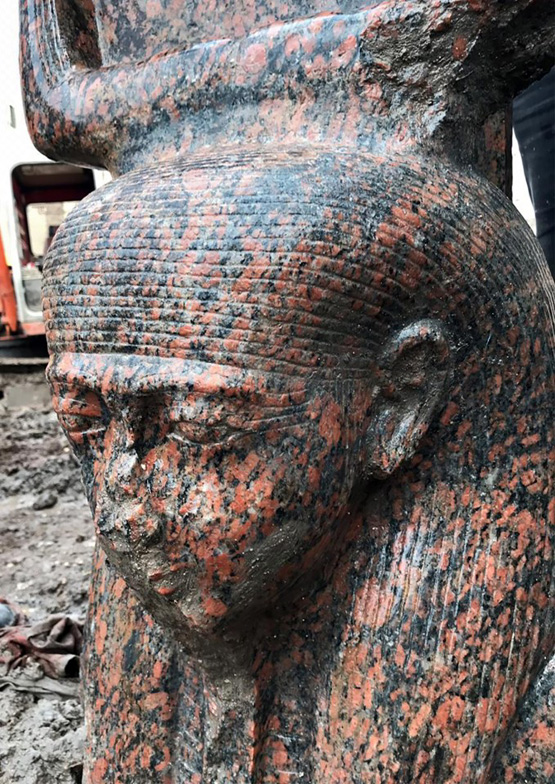

Rare pink statue of Ancient Egyptian king unearthed near pyramids of Giza

The statue was unearthed during excavations at a private plot in the village of Mit Rahina about 20 miles south of Cairo. The artfact depicts Ramses II who ruled Egypt from 1279 to 1213 BC wearing a wig and crown.

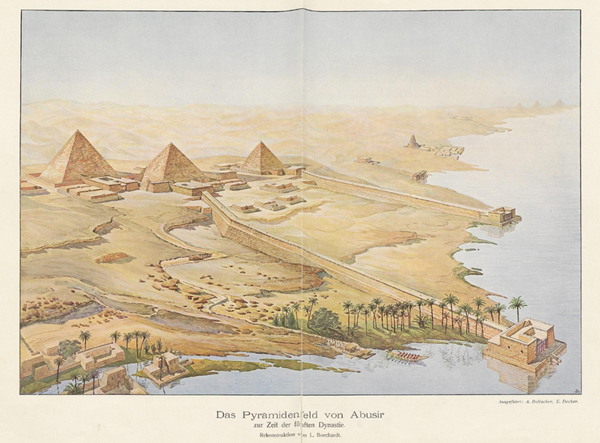

Abusir is an ancient Egyptian archaeological pyramid complex comprising the ruins of four Pharaoh's pyramids dating to the Old Kingdom period and is part of the Pyramid Fields of the Memphis and its Necropolis.

The locality of Abusir took it's turn as the focus of the prestigious western burial rites operating out of the then-capital of Memphis during the Old Kingdom 5th Dynasty. As an elite cemetery, neighbouring Giza had by then "filled up" with the massive pyramids and other monuments of the 4th Dynasty, leading the 5th Dynasty pharaohs to seek sites elsewhere for their own funerary monuments.

A painting by A. Bollacher and E. Decker depicting the pyramids of Neferirkare Kakai (left), Nyuserre Ini (middle) and Sahure (right). Further in the background the figures of sun temples can be made out. In the very far background, three other pyramids can be detected. (1907)

Tomb of unknown queen discovered in Egypt

A Czech archeology team in Egypt has uncovered an intriguing find: the tomb of a previously unknown queen.

The discovery was made in an Old Kingdom necropolis southwest of Cairo in Abusir, home to the pyramid of Pharaoh Neferefre, who ruled 4,500 years ago. The tomb was found in Neferefre’s funeral complex, and it’s believed that the queen was Neferefre’s wife.

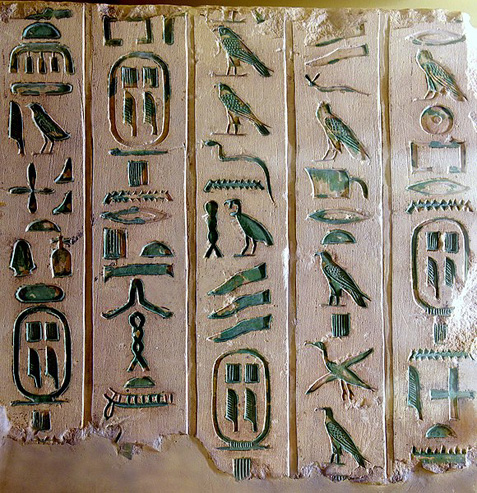

The Pyramid Texts are the oldest ancient Egyptian funerary texts, dating to the late Old Kingdom. They are the earliest known ancient Egyptian religious texts. Written in Old Egyptian the pyramid texts were carved onto the subterranean walls and sarcophagi of pyramids at Saqqara from the end of the Fifth Dynasty and throughout the Sixth Dynasty of the Old Kingdom and into the Eighth Dynasty of the First Intermediate Period. The oldest of the texts have been dated to c. 2400–2300 BC.

| Cartouches of Pepi I and Pyramid Texts. Limestone block fragment from the debris of the north wall of the antechamber within the pyramid of Pepi I at Saqqara. |

|

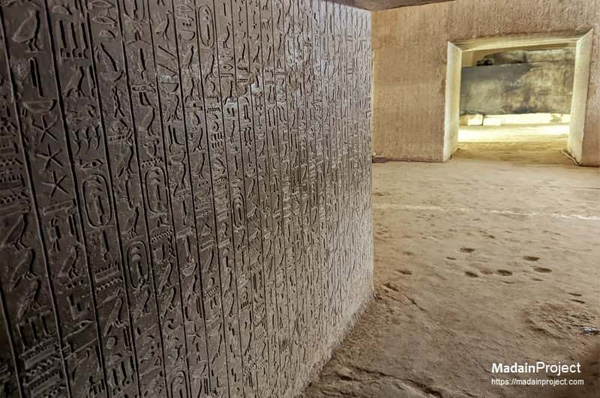

Pyramid Text inscribed on the wall of a subterranean room in Teti's pyramid at Saqqara Unlike the later Coffin Texts and Book of the Dead, the Pyramid Texts were reserved only for the pharaoh and were not illustrated.

|

He built for himself two pyramids at Dahshur and Hawara, becoming the first pharaoh since Sneferu in the Fourth Dynasty to build more than one. Near to his Hawara pyramid is a pyramid for his daughter Neferuptah.

Pyramid of Amenemhat III

A short corridor descends down into the pyramid and leads to a burial chamber. It is not known if the burial chamber is located inside the core of the pyramid or under the ground. There are some niches in the walls of the burial chamber, but their purpose is not known. The sandstone sarcophagus was set into the floor against the West wall.

The burial chamber was made of granite, which was plastered with gypsum. The granite sarcophagus stood to the west, while the canopic chest was stored in a niche in the south of the burial chamber.

HEADLESS PYRAMID

Menkauhor's

"Headless Pyramid"

North Saqqara

The completely destroyed pyramid in North Saqqara, which lies on the farthest edge of the desert plateau east of Teti's mortuary temple, is sometimes attributed to Menkauhor. Local people named its "Headless Pyramid". In the rubble of the pit for the burial chamber Maspero found fragments of pink granite and even a sarcophagus lid of bluish gray stone.

Shepseskaf

built his burial tomb as a large mastaba at Saqqara necropolis.

This building structure was excavated in 1858 by Auguste Mariette.

However it was discovered by Gustave Jéquier that this

tomb belonged to Pharaoh Shepseskaf through the excavation of

a stele which revealed the involvement of this Egyptian king

in the construction of this building.

Shepseskaf shifted away from the tradition of his predecessors

of building pyramids for themselves. This choice of this Pharaoh

is still a strange fact to historians and has given rise to several

assumptions. The base of this mastaba was laid precisely like

that of a pyramid, leading some Egyptologists to conclude that

due to the untimely death of Shepseskaf he could not complete

his pyramid and later on his family members turned it into a

mere mastaba, a much simpler building than a pyramid. However

some scholars believe that Shepseskaf himself might have wanted

a simple burial tomb, unlike his predecessors, which made him

shift the site of his tomb from Giza to Saqqara, a lesser-known

necropolis. There is a broken pyramid temple in the eastern part

of this complex and a portion of the previously existing causeway,

proving the initial planning of building a pyramid only.

Mortuary Temple Of Hatshepsut, Luxor

Memphite Necropolis aka Pyramid Fields

It includes the pyramid complexes of Giza, Abusir, Saqqara and Dahshur, and is listed as the UNESCO World Heritage Site of Memphis and its Necropolis. Most of the pyramids of the Old Kingdom were built here along with many mastabas and other tombs.

|

As part of his work Perring created several maps, plans and cross-sections of the pyramids at Abu Roasch, Gizeh, Abusir, Saqqara and Dahshur. He was the first to explore the interior of the Pyramid of Userkaf at Saqqara in 1839 through a robber's tunnel first discovered in 1831. Perring thought the pyramid belonged to Djedkare. The pyramid was first correctly identified by Egyptologist Cecil Firth in 1928 though Firth died in 1931 and excavations there only recommenced in 1948 under Jean-Philippe Lauer. Perring opened the northern entrance into the Bent Pyramid and added some graffiti inside the nearby Red Pyramid at Dahshur, which can still be viewed today. Perring's work resulted in his three-volume "The Pyramids of Gizeh", published in 1839 to 1842. |

National Bibliography 1885-1990

Where it is stated that Perring's research resulted in furnishing the names of six Egyptian kings till then unknown to historians.

Cave Below Giza - verify this

|

John Shae Perring (1813–1869) was a British engineer, anthropologist and Egyptologist, most notable for his work excavating and documenting Egyptian pyramids. |

Saqqara is the site of the first Egyptian pyramid, the Pyramid of Djoser and thus the first pyramid field in the Memphite Necropolis, established in the 27th Century BC during the Third Dynasty with another 16 pyramids built over the centuries though the Fifth Dynasty. However, the site was used for burials at least as early as the First Dynasty ca. 32nd Century BC and remained in almost continuous use as a cemetery for 3000 years until the Ptolemaic Period 30 BC.

Saqqara contains the oldest complete stone building complex known in history, the Pyramid of Djoser, built during the Third Dynasty. Another sixteen Egyptian kings built pyramids at Saqqara, which are now in various states of preservation. High officials added private funeral monuments to this necropolis during the entire Pharaonic period. It remained an important complex for non-royal burials and cult ceremonies for more than 3000 years, well into Ptolemaic and Roman times.

Dahshur is an ancient Egyptian pyramid complex and necropolis. It is known chiefly for several pyramids, mainly Senefru's Bent Pyramid and the Red Pyramid which are among the oldest, largest and best preserved in Egypt, built from 2613 to 2589 BC.

The Red Pyramid was the third pyramid built by Old Kingdom Pharaoh Sneferu and was built 2575–2551 BC.

Of the largely robbed equipment (traces of a fire) only scant rinders of the mummy of Snefru were found (according to T. Schneider).

In 1950, fragments of human remains were found in the passage way of the Red Pyramid and examined by Dr. Ahmed Mahmud el Batrawi. The remains and wrappings were found to be consistent with 4th dynasty mummification techniques. Whether these humain remains belong to Sneferu is uncertain.

The Red Pyramid is the largest of the pyramids located at the Dahshur necropolis. It is believed to be Egypt's first successful attempt at constructing a "true" smooth-sided pyramid.

The earliest stone sarcophagi were used by Egyptian pharaohs of the 3rd dynasty which reigned from about 2686 to 2613 .C.

Sekhemkhet's pyramid is sometimes referred to as the "Buried Pyramid

Sekhemkhet's pyramid is sometimes referred to as the "Buried Pyramid" and was first excavated in 1952 by Egyptian archaeologist Zakaria Goneim. A sealed sarcophagus was discovered beneath the pyramid, but when opened was found to be empty.

The burial chamber has a base measurement of 29 ft x 17 ft and a height of 15 ft. It was also left unfinished, but surprisingly a nearly completely arranged burial was found. The sarcophagus in the midst of the chamber is made of polished alabaster and shows an unusual feature: its opening lies on the front side and is sealed by a sliding door, which was still plastered with mortar when the sarcophagus was found. The sarcophagus was empty, however and it remains unclear whether the site was ransacked after burial or whether King Sekhemkhet was buried elsewhere.

Closed to the public because of its dangerous condition, the unfinished pyramid of Zoser’s successor Sekhemkhet (2648–2640 BC) is a short distance west of the ruined Monastery St Jeremiah. The project was abandoned for unknown reasons when the great limestone enclosure wall was only 3m high, despite the fact that the architects had already constructed the underground chambers in the rock beneath the pyramid as well as the deep shaft of the south tomb.

An unused travertine sarcophagus was found in the sealed burial chamber, and a quantity of gold and jewellery and a child’s body were discovered in the south tomb. Recent surveys have also revealed another mysterious large complex to the west of Sekhemkhet’s enclosure, but this remains unexcavated.

Mysterious ‘Sarcophagus’ of Sekhemkhet said to have been carved from one solid block of ‘Egyptian alabaster’ with sliding door. Dated from 2649 – 2643 BC

"In the middle of a rough-cut chamber lay a magnificent sarcophagus of pale, golden, translucent alabaster" under the Sekhemkhet Pyramid at Saqqara.” The only opening was sliding panel at one end, slid into position from the top.

When found in 1954 the box was completely sealed--and no body was found inside. The pyramid was so named because they found the title "Sekhemkhet" on the lids of jars found at the same location.

Ancient Priest's Tomb Painting Discovered Near Great Pyramid at Giza

2014

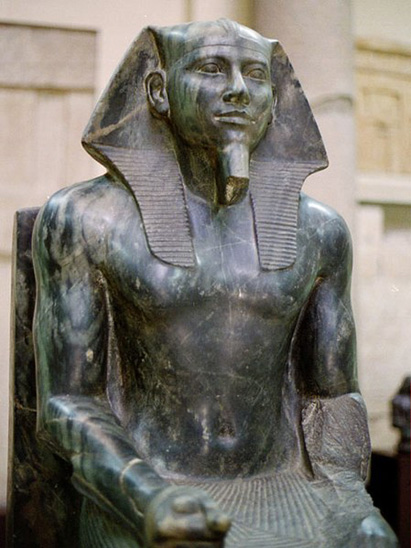

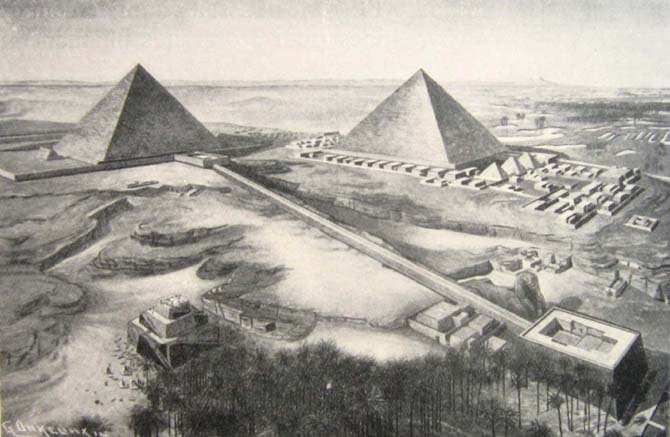

Drawing of Khafre's pyramid complex. A causeway connected the Valley Temple (bottom-right) to the Pyramid Temple (top-left). Photo taken in 1910.

Hotepsekhemwy is the Horus name of an early Egyptian Pharaoh who was the founder of the Second Dynasty of Egypt.

Lost Technologies of Ancient Egyptian Architecture: Beyond the Pyramids

You’ve probably heard about the Great Pyramids of Egypt, but they’re just the tip of the architectural iceberg. Ancient Egyptian builders possessed technological capabilities that continue to baffle modern engineers, from impossibly precise stone joints to sophisticated climate control systems in underground tombs. While you’ll find countless theories about how these wonders were achieved, the actual methods remain tantalizingly out of reach. The true mystery lies not in the massive monuments themselves, but in the lost tools and techniques that made such architectural mastery possible. Let’s explore the lesser-known innovations that have vanished into the sands of time.

Precision Engineering in Temple Construction

Ancient Egyptian engineers achieved remarkable structural precision that continues to mystify modern architects and archaeologists. You’ll find incredibly tight stone joints in temple walls, with tolerances under 0.5mm. They’ve created perfectly level foundations across massive temple complexes, using sophisticated plumb bobs and measuring tools. These structures maintain their integrity even after withstanding millennia of earthquakes and climate stresses.

Advanced Ancient Surveying Methods

While modern surveyors rely on GPS and laser technology, Egyptian builders developed sophisticated surveying techniques that achieved remarkable accuracy across vast distances. You’ll find they used plumb bobs, measuring ropes, and wooden stakes to create perfect right angles. They mastered the 3-4-5 triangle principle and implemented a system of ground-based grids to ensure precise structural alignment and level foundations.

Hidden Tomb Ventilation Systems

Inside elaborate Egyptian tombs, intricate networks of air shafts and ventilation channels demonstrate remarkable environmental engineering capabilities. You’ll find precisely angled shafts that utilize thermal convection principles, creating natural airflow patterns. These systems maintain consistent temperatures of 22-24°C and regulate humidity levels at 40%, preserving artifacts and wall paintings while providing breathable air for workers and visitors.

Copper Tools and Stone Mastery

Egyptian craftsmen achieved remarkable precision in stonework using copper-based tools that shouldn’t have been capable of such feats. You’ll find they worked granite and diorite, materials measuring 7-8 on Mohs scale, with copper tools rating only 3.5. They enhanced copper’s effectiveness through work-hardening techniques and likely used abrasive powders like quartz to amplify cutting power against harder stones.

Giovanni Belzoni, 1778 – 1823 was a prolific Italian explorer and pioneer archaeologist of Egyptian antiquities. He is known for his removal to England of the 7-ton bust of Ramesses II, the clearing of sand from the entrance of the great temple at Abu Simbel, the discovery and documentation of the tomb of Seti I including the sarcophagus of Seti I and the first to penetrate into the Pyramid of Khafre, the second pyramid of the Giza complex.

Beneath a lake lies the ruins of the city of Naukratis, a Greek-founded city, which served as a trading port somewhere around 620 BC.

100–1 BC

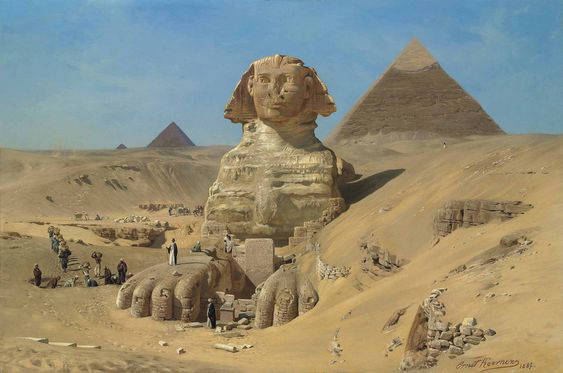

The Excavation of the Sphinx [1887]

Artist Ernst

Karl Eugen Koerner

Trained in Berlin, Ernst Koerner (1846-1927) travelled widely

throughout northern Europe before making a trip to Egypt in 1873

that would determine the course of the rest of his career. Captivated

by the landscapes of the Eastern Mediterranean, Koerner became

famous for his beautifully detailed depictions of architecturally

important sites, particularly in Turkey and Egypt. This picture

captures not only an iconic monument, but a monumental moment

in time, as the Sphinx is being excavated.

Egypt’s Oldest Papyri Detail Great Pyramid Construction

Egypt’s oldest papyrus fragments which detail the construction

of the Great Pyramid of Giza have gone on public display in Cairo.

|

In 2013 a joint team of French and Egyptian archaeologists discovered a remarkable find in a cave at the ancient Red Sea port of Wadi el-Jarf—hundreds of inscribed papyrus fragments that were the oldest ever unearthed in Egypt. As Egyptologists Pierre Tallet and Gregory Marouard detailed in a 2014 article in the journal Near Eastern Archaeology, the ancient texts they discovered included a logbook from the 27th year of the reign of the pharaoh Khufu that described the construction of the Great Pyramid of Giza. The hieroglyphic letters inscribed in the logbook were written more than 4,500 years ago by a middle-ranking inspector named Merer who detailed over the course of several months the construction operations for the Great Pyramid which was nearing completion and the work at the limestone quarries at Tura on the opposite bank of the Nile River. Merer’s logbook, written in a two-column daily timetable, reports on the daily lives of the construction workers and notes that the limestone blocks exhumed at Tura which were used to cover the pyramid’s exterior were transported by boat along the Nile River and a system of canals to the construction site, a journey that took between two and three days. |

The 32nd century BC lasted from the year 3200 BC to 3101 BC. That’s about 5,200 years ago

The Forgotten City Beneath Egypt

A short tale about the lost city of Naukratis of Greek origin drowned beneath the Nile

Sunken Egypt

Heracleion

Canopus

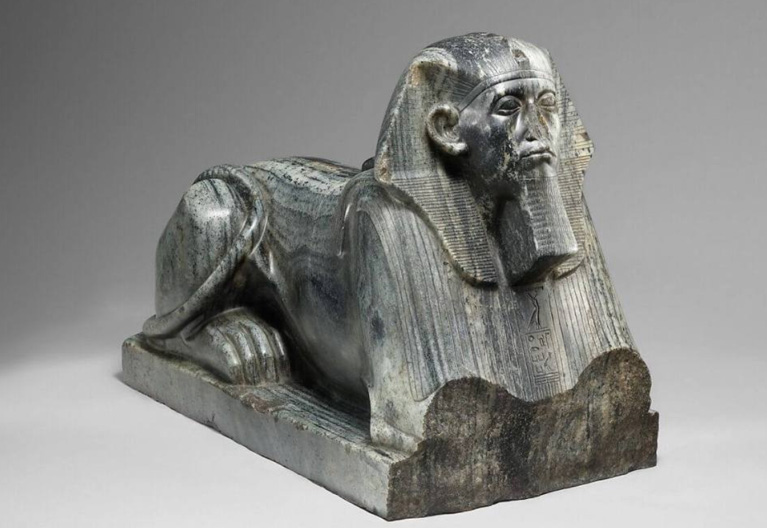

The Sphinx of Memphis is a stone sphinx located near the remains of Memphis, Egypt. The carving was believed to take place between 1700 and 1400 BC, which was during the 18th Dynasty. It is unknown which pharaoh is being honored and there are no inscriptions to supply information. The facial features imply that the Sphinx is honoring Hatshepsut or Amenhotep II or Amenhotep III.

It’s 26 feet/8 meters long and 13 feet/4 meters high.

It’s carved from Calcite and is the largest Calcite statue in the world. It’s the only Sphinx with the curious striations or lines on it which you can see in the closeup.

Great

Sphinx of Tanis

The Louvre Museum’s Egyptian Department contains over 50,000

pieces housed in 20 rooms. Here’s one of them: The Great

Sphinx of Tanis, from 2000 BC, which is one of the largest sphinxes

outside of Egypt. Found in 1825 among the ruins of the Temple

of Amun at Tanis (the capital of Egypt during the 21st and 22nd

dynasties), it’s inscribed with the names of the Pharaohs

Ammenemes II (1929-1895 BC), Merneptah (1212-02 BC) and Shoshenq

I (945-24 BC).

The restoration took place on the grounds of the Crystal Palace

in Sydenham Hill, London, which you can see in the old photograph.

Many people think the Great Sphinx is from 12,000 years ago and from a lost civilization but then why are there similar Sphinxes like this that a smaller size in other major locations like Memphis and Tanis, two former capital cities of the Ancient Egyptians?

Founded in 1882

Egypt Exploration Society

The Naqada Regional Archaeological Survey and Site Management Project

Egypt Exploration Society

100–1

BCE

Egypt, Greco-Roman period (332 BCE–395 CE), Ptolemaic dynasty

(305–30 BCE)

Gold and semi-precious stones

Overall: 3 x 2.8 cm (1 3/16 x 1 1/8 in.)